— Feature

Sol Cycle

Throughout history, human-scale architecture has been a tool for understanding our place in the universe.

As a milestone for measuring time, the winter solstice is an opportunity to reflect, recalibrate, and look ahead. The shortest day of the year is so meaningful that, across epochs and cultures, it has compelled humans to create monuments whose engineering and symbolism we still do not fully understand.

Goseck Circle is the world’s oldest known solar observatory. For a 200-year period that began around 4900 BCE, Neolithic farmers in modern-day Germany and Austria created Goseck Circle and many similar enclosures using wood palisades.

In 2002, eleven years after a circular mound appeared in an aerial photo of a wheatfield, archaeologists Peter Biehl and Francois Bertemes conducted an excavation as an exercise for their students at Halle-Wittenberg University. Using GPS and in-situ evidence, the professors determined that the circle’s southeast and southwest gates aligned perfectly to sunrise and sunset at winter solstice. The discovery was made public the following year and, by 2005, the pair of concentric circles had been reconstructed with 2,000 oak posts.

In 1699, Charles Campbell did not think much of the mound of stones he had just uncovered beneath his estate outside Dublin — that is, until further probing revealed a large, decorated stone guarding an entrance to a passage. Over years of excavation and research, antiquarians determined that this acre-spanning dome, dubbed Newgrange, was built of 200,000 tons of material in 3200 BCE as a passage tomb.

While theories about who was buried at Newgrange, and why, proliferated almost from the day of its discovery, it would not be until 1967 when archaeologist Michael O’Kelly learned that the dome had been calibrated to the winter solstice. After repeatedly hearing lore that that sunrise penetrates the dome’s main chamber, O’Kelly placed himself within the cruciform-shaped compartment before dawn and waited. The emerging sunlight hit a small, theretofore-unseen “roof-box,” traveled 62 feet into the main chamber, and illuminated it for 17 minutes. O’Kelly was the first person to witness this shaft of daylight in more than five millennia, and today the winners of an annual lottery are permitted into Newgrange to experience the profundity directly.

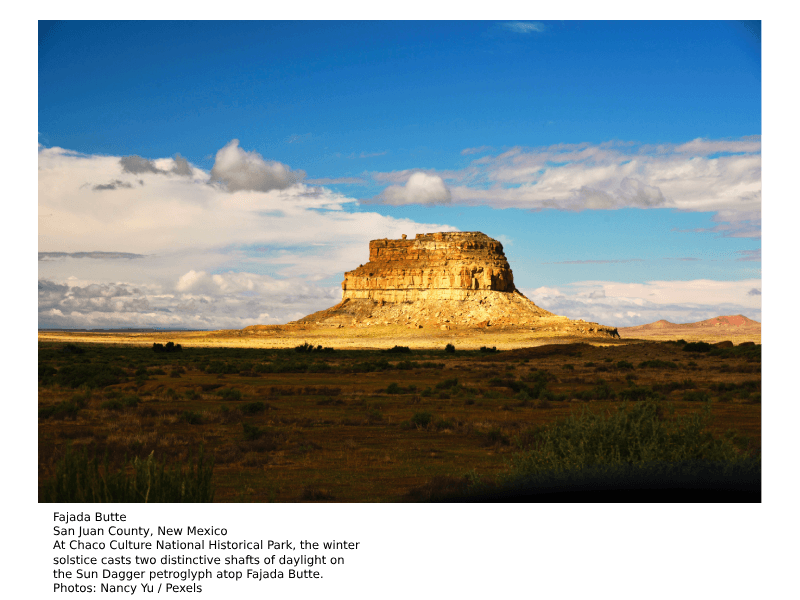

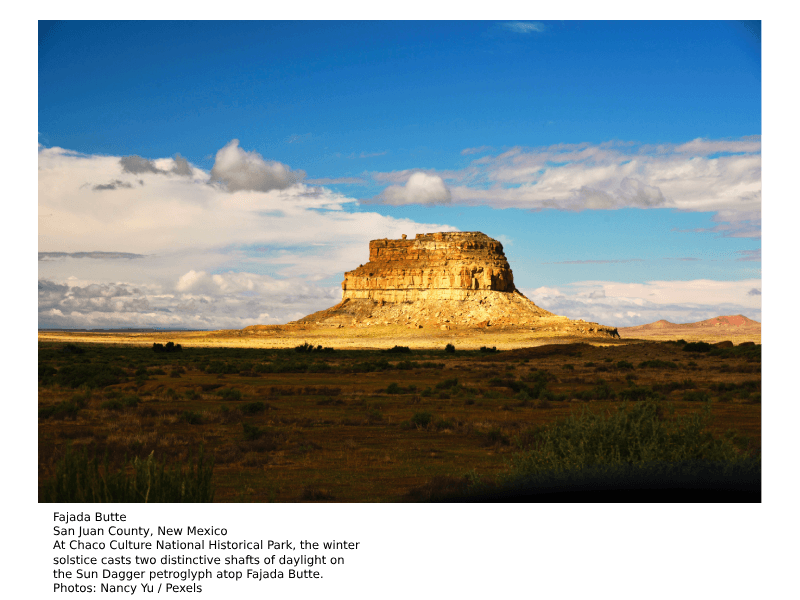

Standing at the entrance to New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon, Fajada Butte is an unlikely place to find evidence of pre-Columbian culture: the surrounding valley is characterized by long winters and minimal annual rainfall. Defying expectation are the many traces of Pueblo, Hopi, and Navajo life. A ramp equal in length to two and a half football fields was carved into the butte, and summit-area dwellings were occupied between 850 and 1250 AD according to analysis of pottery fragments.

When community organizer and artist Anna Sofaer visited Chaco Canyon as a volunteer recording rock art in June 1977, a pair of spiral petroglyphs on a southeastern facing cliff near the top of Fajada Butte caught her eye. Three large stone slabs surrounding the cliff wall manipulated the light and shadow that reached the cliffside, and at noontime, a shaft of daylight seemed to bisect the larger of the two spirals. Further study showed that the sun’s rays reached the exact center of the petroglyph at summer solstice, and that they bracketed the spiral inscription during the winter solstice. Now known as the Sun Dagger, the site may also mark the passage of the lunar cycle, and supports the theory that Chacoan people centered commerce, ceremonies, and social exchange at Fajada Butte thanks to the landform’s spiritual resonance.

Although the world’s ancient solar observatories were built for longevity, they were used by their makers for comparatively brief stretches. The Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu is no exception. This sprawling UNESCO World Heritage site located at the intersection of the Peruvian Andes and the Amazon Basin was erected in the 1400s, and the Inca Empire abandoned it after its fall to Spanish colonists just a century later.

The enormity of Machu Picchu is a testament to the innovation and industry of the Incan people. So big is the community, that it is divided into urban and farming sectors that meet at a central square. Meanwhile, Machu Picchu’s religious buildings attest to all residents’ interest in agricultural advancement. Within this quarter of the urban sector stands the Temple of the Sun, Machu Picchu’s one curved building whose two windows are aligned to the solstices and equinoxes. Only the emperor, noble family, and highest-ranking priests were allowed to enter the Temple of the Sun, and only priests with astronomical training were allowed to oversee many of Machu Picchu’s houses of worship, given the buildings’ coordination to the seasons.

As a milestone for measuring time, the winter solstice is an opportunity to reflect, recalibrate, and look ahead. The shortest day of the year is so meaningful that, across epochs and cultures, it has compelled humans to create monuments whose engineering and symbolism we still do not fully understand.

Goseck Circle is the world’s oldest known solar observatory. For a 200-year period that began around 4900 BCE, Neolithic farmers in modern-day Germany and Austria created Goseck Circle and many similar enclosures using wood palisades.

In 2002, eleven years after a circular mound appeared in an aerial photo of a wheatfield, archaeologists Peter Biehl and Francois Bertemes conducted an excavation as an exercise for their students at Halle-Wittenberg University. Using GPS and in-situ evidence, the professors determined that the circle’s southeast and southwest gates aligned perfectly to sunrise and sunset at winter solstice. The discovery was made public the following year and, by 2005, the pair of concentric circles had been reconstructed with 2,000 oak posts.

In 1699, Charles Campbell did not think much of the mound of stones he had just uncovered beneath his estate outside Dublin — that is, until further probing revealed a large, decorated stone guarding an entrance to a passage. Over years of excavation and research, antiquarians determined that this acre-spanning dome, dubbed Newgrange, was built of 200,000 tons of material in 3200 BCE as a passage tomb.

While theories about who was buried at Newgrange, and why, proliferated almost from the day of its discovery, it would not be until 1967 when archaeologist Michael O’Kelly learned that the dome had been calibrated to the winter solstice. After repeatedly hearing lore that that sunrise penetrates the dome’s main chamber, O’Kelly placed himself within the cruciform-shaped compartment before dawn and waited. The emerging sunlight hit a small, theretofore-unseen “roof-box,” traveled 62 feet into the main chamber, and illuminated it for 17 minutes. O’Kelly was the first person to witness this shaft of daylight in more than five millennia, and today the winners of an annual lottery are permitted into Newgrange to experience the profundity directly.

Standing at the entrance to New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon, Fajada Butte is an unlikely place to find evidence of pre-Columbian culture: the surrounding valley is characterized by long winters and minimal annual rainfall. Defying expectation are the many traces of Pueblo, Hopi, and Navajo life. A ramp equal in length to two and a half football fields was carved into the butte, and summit-area dwellings were occupied between 850 and 1250 AD according to analysis of pottery fragments.

When community organizer and artist Anna Sofaer visited Chaco Canyon as a volunteer recording rock art in June 1977, a pair of spiral petroglyphs on a southeastern facing cliff near the top of Fajada Butte caught her eye. Three large stone slabs surrounding the cliff wall manipulated the light and shadow that reached the cliffside, and at noontime, a shaft of daylight seemed to bisect the larger of the two spirals. Further study showed that the sun’s rays reached the exact center of the petroglyph at summer solstice, and that they bracketed the spiral inscription during the winter solstice. Now known as the Sun Dagger, the site may also mark the passage of the lunar cycle, and supports the theory that Chacoan people centered commerce, ceremonies, and social exchange at Fajada Butte thanks to the landform’s spiritual resonance.

Although the world’s ancient solar observatories were built for longevity, they were used by their makers for comparatively brief stretches. The Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu is no exception. This sprawling UNESCO World Heritage site located at the intersection of the Peruvian Andes and the Amazon Basin was erected in the 1400s, and the Inca Empire abandoned it after its fall to Spanish colonists just a century later.

The enormity of Machu Picchu is a testament to the innovation and industry of the Incan people. So big is the community, that it is divided into urban and farming sectors that meet at a central square. Meanwhile, Machu Picchu’s religious buildings attest to all residents’ interest in agricultural advancement. Within this quarter of the urban sector stands the Temple of the Sun, Machu Picchu’s one curved building whose two windows are aligned to the solstices and equinoxes. Only the emperor, noble family, and highest-ranking priests were allowed to enter the Temple of the Sun, and only priests with astronomical training were allowed to oversee many of Machu Picchu’s houses of worship, given the buildings’ coordination to the seasons.