— Feature

Check, Please

Over a 400-year history, gingham has become the pattern of the people.

Today it is the pattern of American picnic blankets and restaurant tablecloths, of prairie dresses and button-downs. Yet gingham wasn’t always so thoroughly engrained in American culture. Nor was it even a three-toned check. As culture historian Jude Stewart explains in the 2015 book Patternalia, “Gingham was first named for the weave, a simple twill [that] produced no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ side.” The weave also was likely invented in India, as most scholars point to the Malay word genggang for gingham’s root. The term literally translates to “striped” and indeed, the cotton cloth featured stripes when Dutch merchants first imported it to Europe in the 17th century.

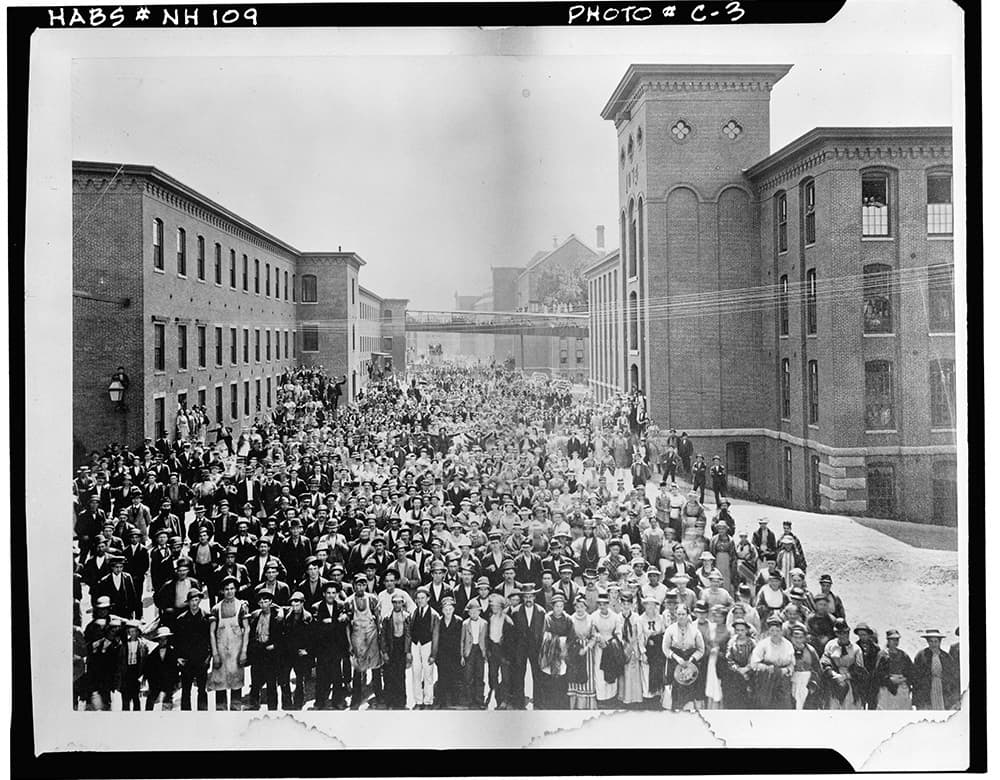

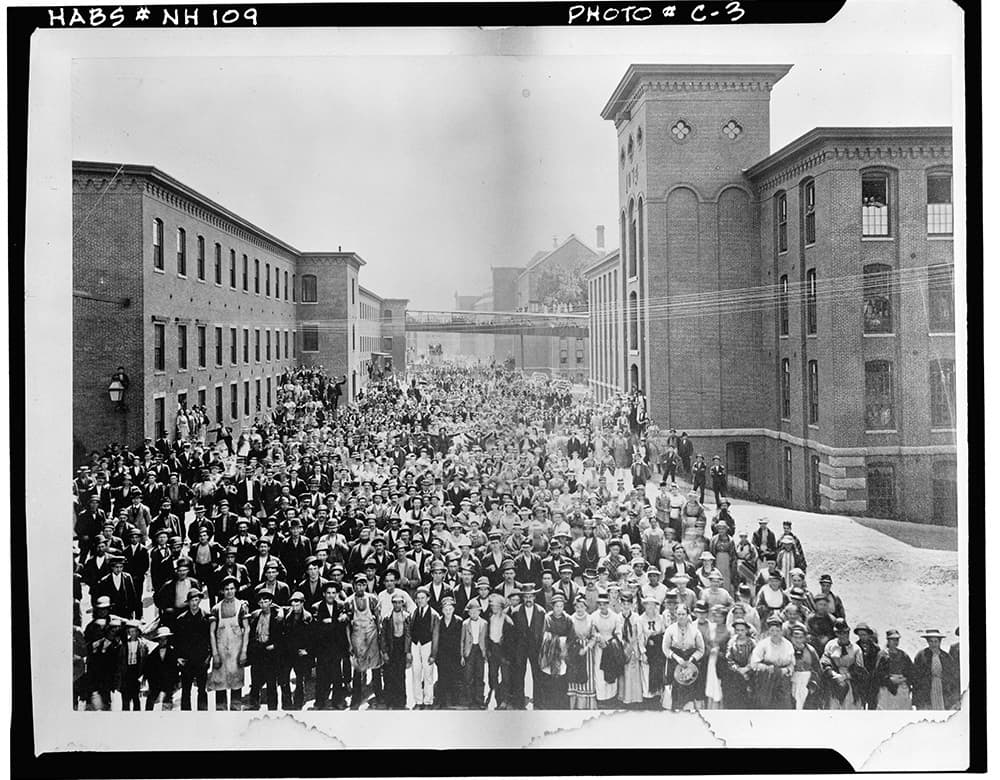

How did this metaphorical leopard change its spots? Gingham’s visual evolution to a checkered pattern coincided with its shift to Western production, as seen in artifacts and images from the Georgian and Victorian eras. Industrial production of textiles has its roots in Manchester, England, thanks to the wool and fustian weavers who had called the city home since the 1500s. When the British Empire outlawed cotton manufacturing in India after colonization in 1757, production of the cloth centered in Manchester, where 99 cotton-spinning enterprises had sprouted by 1830. Supplied by cotton plantations in the South, American textile industrialization had begun to soar at approximately the same time, while taking its style cues from the British. On both sides of the Atlantic, gingham check rung in the 19th century.

While striped gingham, not to mention the occasional plaid, did not disappear overnight, a glimpse of the 1897 Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog explains why those other patterns faded from popularity. The so-called Book of Bargains featured only one striped gingham, and the yardage cost a multiplier more than the “apron checks” and “dress ginghams” that Sears, Roebuck had stocked. Simply put, check was cheap, and consumers voted for it with their wallets.

Checkered gingham was an affordable long-term investment, too. It could take a beating and conceal stains and wrinkles or be reversed for a do-over. It is little wonder, then, that it became the textile of American work.

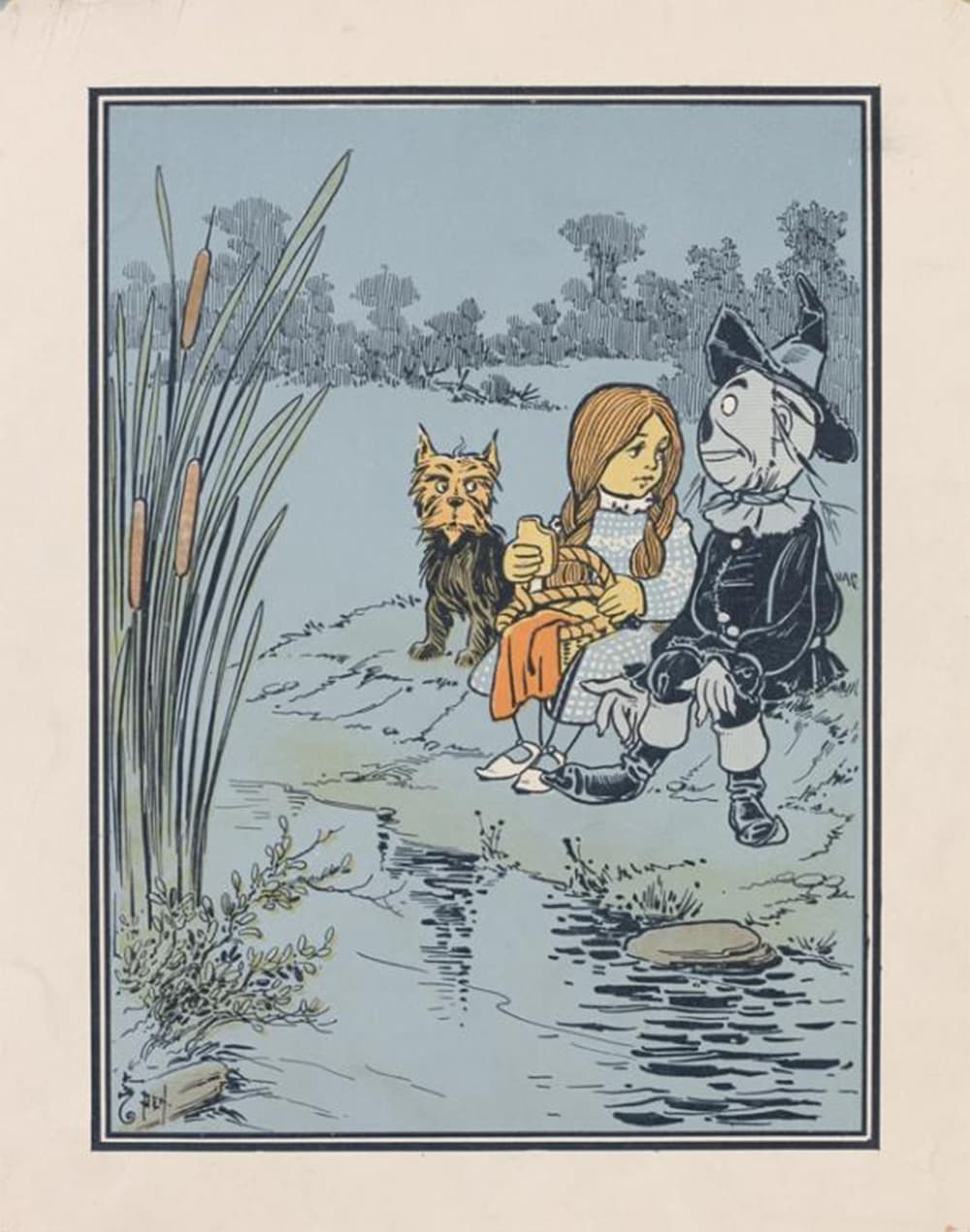

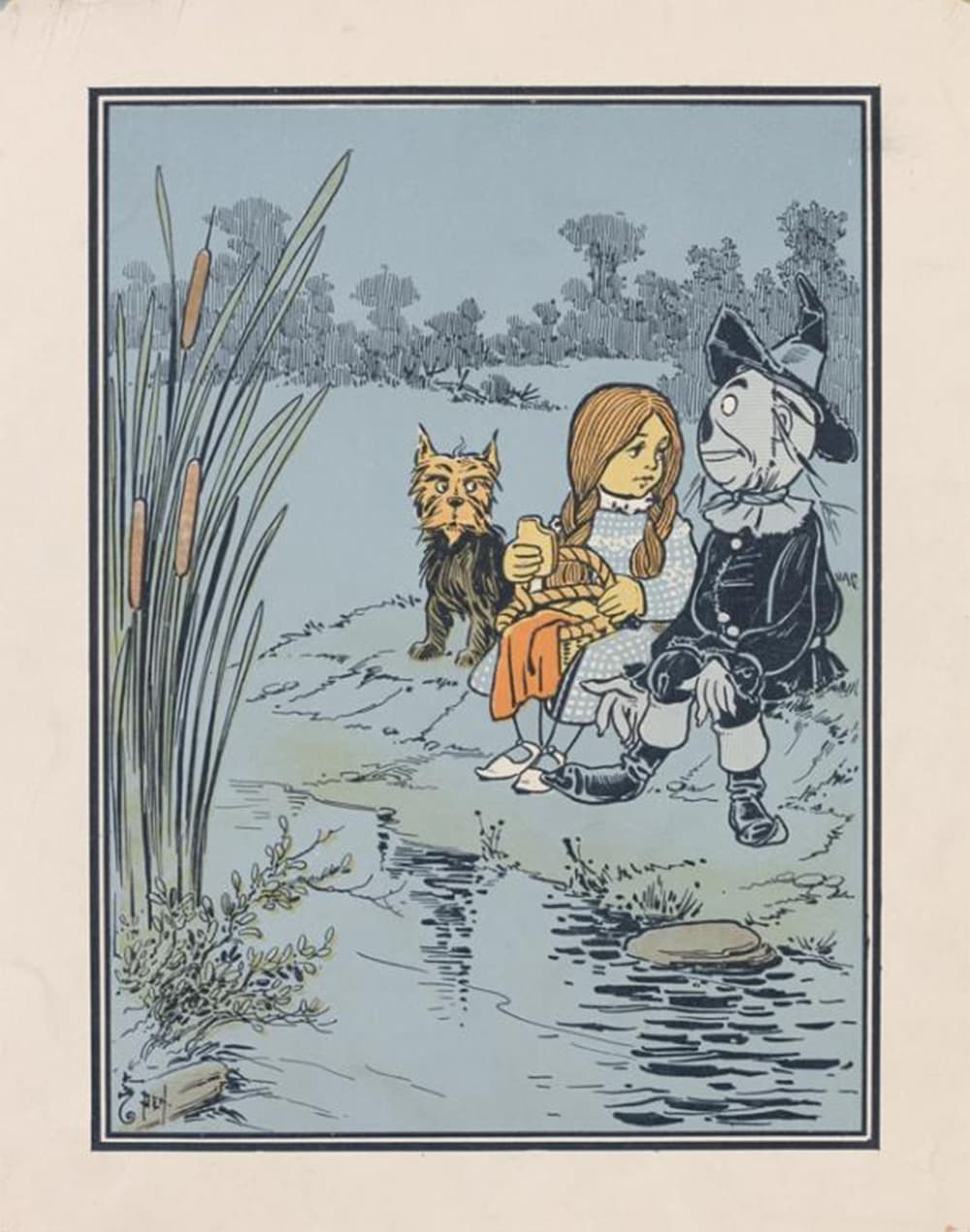

But popular culture in late-Victorian-era America did more than bear witness to checkered gingham’s place in the lives of laborers and housewives. It also worked mightily to enshrine the textile as a symbol of productivity, optimism, and wholesomeness — “redolent of summertime and the prairies,” as Stewart phrased it in Patternalia. In 1915, Dorothy Donnell Calhoun introduced readers to a loving retired couple in Blue Gingham Folks, and two years prior the musical theater composer Manuel Klein gushed over the girl in a gingham gown whose “grace and dignity” outshone “city girls with silks and laces.” And, of course, there’s Dorothy Gale, who dreams of returning from Oz to her family and home in Kansas. “Dorothy had only one other dress, but that happened to be clean, and was hanging on a peg beside her bed. It was gingham, with checks of white and blue; and although the blue was somewhat faded with many washings, it was still a pretty frock,” L. Frank Baum wrote of the morning his The Wonderful Wizard of Oz heroine would take her first steps along the yellow brick road.

Gingham was simultaneously changing with the times, too. In 1916, Kansas City designer Nelly Don introduced a mass-produced housedress in pink gingham, selling 216 of them at Peck’s Dry Goods Company on day one. According to scholars Mikyoung Whang and Sherry Haar, “the grand lady of the garment industry” was one of the most successful female entrepreneurs in early-20th-century America and her product freed buyers from making their wardrobe from patterns, intimating a new role for middle-class women in American society. New interpretations of gingham became more visible thereafter. Journalist Mark Dent observed that gingham outfits helped define Doris Day’s alluring persona. The pattern became part of 1960s British youth culture when rebellious fashion designer Barbara Hulanicki published a gingham shift dress in The Daily Mirror, and Comme des Garçons designer Rei Kawakubo’s lumpy gingham dresses for spring/summer 1997 ignited conversations about feminism, gender, and body image that are ongoing. Fast forward to now, and gingham is adorning campsites and campuses, hanging in lockers as well as boutiques, expressing nostalgia or subversion. It adapts, therefore it is indispensable.

Today it is the pattern of American picnic blankets and restaurant tablecloths, of prairie dresses and button-downs. Yet gingham wasn’t always so thoroughly engrained in American culture. Nor was it even a three-toned check. As culture historian Jude Stewart explains in the 2015 book Patternalia, “Gingham was first named for the weave, a simple twill [that] produced no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ side.” The weave also was likely invented in India, as most scholars point to the Malay word genggang for gingham’s root. The term literally translates to “striped” and indeed, the cotton cloth featured stripes when Dutch merchants first imported it to Europe in the 17th century.

How did this metaphorical leopard change its spots? Gingham’s visual evolution to a checkered pattern coincided with its shift to Western production, as seen in artifacts and images from the Georgian and Victorian eras. Industrial production of textiles has its roots in Manchester, England, thanks to the wool and fustian weavers who had called the city home since the 1500s. When the British Empire outlawed cotton manufacturing in India after colonization in 1757, production of the cloth centered in Manchester, where 99 cotton-spinning enterprises had sprouted by 1830. Supplied by cotton plantations in the South, American textile industrialization had begun to soar at approximately the same time, while taking its style cues from the British. On both sides of the Atlantic, gingham check rung in the 19th century.

While striped gingham, not to mention the occasional plaid, did not disappear overnight, a glimpse of the 1897 Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog explains why those other patterns faded from popularity. The so-called Book of Bargains featured only one striped gingham, and the yardage cost a multiplier more than the “apron checks” and “dress ginghams” that Sears, Roebuck had stocked. Simply put, check was cheap, and consumers voted for it with their wallets.

Checkered gingham was an affordable long-term investment, too. It could take a beating and conceal stains and wrinkles or be reversed for a do-over. It is little wonder, then, that it became the textile of American work.

But popular culture in late-Victorian-era America did more than bear witness to checkered gingham’s place in the lives of laborers and housewives. It also worked mightily to enshrine the textile as a symbol of productivity, optimism, and wholesomeness — “redolent of summertime and the prairies,” as Stewart phrased it in Patternalia. In 1915, Dorothy Donnell Calhoun introduced readers to a loving retired couple in Blue Gingham Folks, and two years prior the musical theater composer Manuel Klein gushed over the girl in a gingham gown whose “grace and dignity” outshone “city girls with silks and laces.” And, of course, there’s Dorothy Gale, who dreams of returning from Oz to her family and home in Kansas. “Dorothy had only one other dress, but that happened to be clean, and was hanging on a peg beside her bed. It was gingham, with checks of white and blue; and although the blue was somewhat faded with many washings, it was still a pretty frock,” L. Frank Baum wrote of the morning his The Wonderful Wizard of Oz heroine would take her first steps along the yellow brick road.

Gingham was simultaneously changing with the times, too. In 1916, Kansas City designer Nelly Don introduced a mass-produced housedress in pink gingham, selling 216 of them at Peck’s Dry Goods Company on day one. According to scholars Mikyoung Whang and Sherry Haar, “the grand lady of the garment industry” was one of the most successful female entrepreneurs in early-20th-century America and her product freed buyers from making their wardrobe from patterns, intimating a new role for middle-class women in American society. New interpretations of gingham became more visible thereafter. Journalist Mark Dent observed that gingham outfits helped define Doris Day’s alluring persona. The pattern became part of 1960s British youth culture when rebellious fashion designer Barbara Hulanicki published a gingham shift dress in The Daily Mirror, and Comme des Garçons designer Rei Kawakubo’s lumpy gingham dresses for spring/summer 1997 ignited conversations about feminism, gender, and body image that are ongoing. Fast forward to now, and gingham is adorning campsites and campuses, hanging in lockers as well as boutiques, expressing nostalgia or subversion. It adapts, therefore it is indispensable.