— Feature

Missed Media

A Reflection on Drafting by Hand

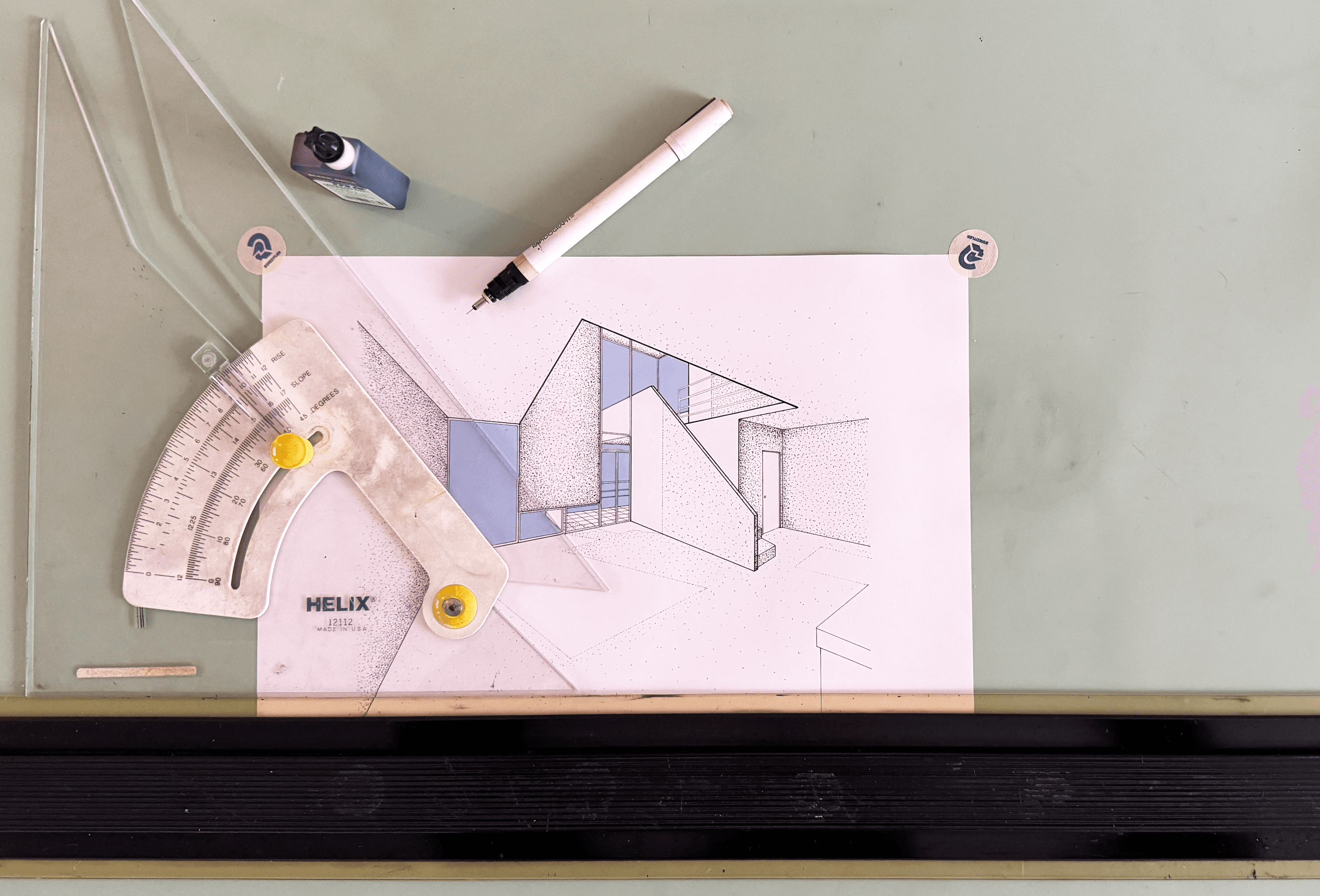

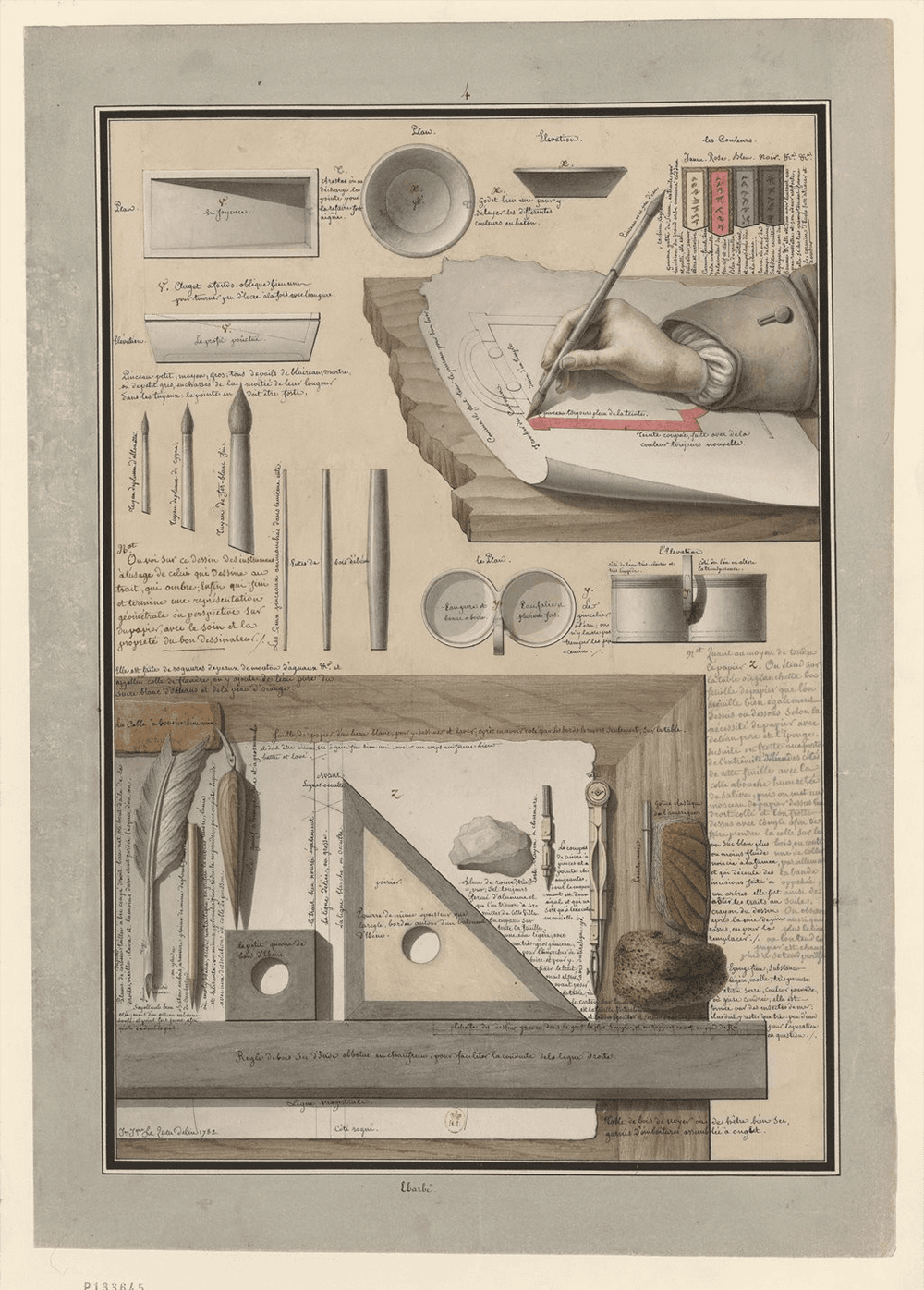

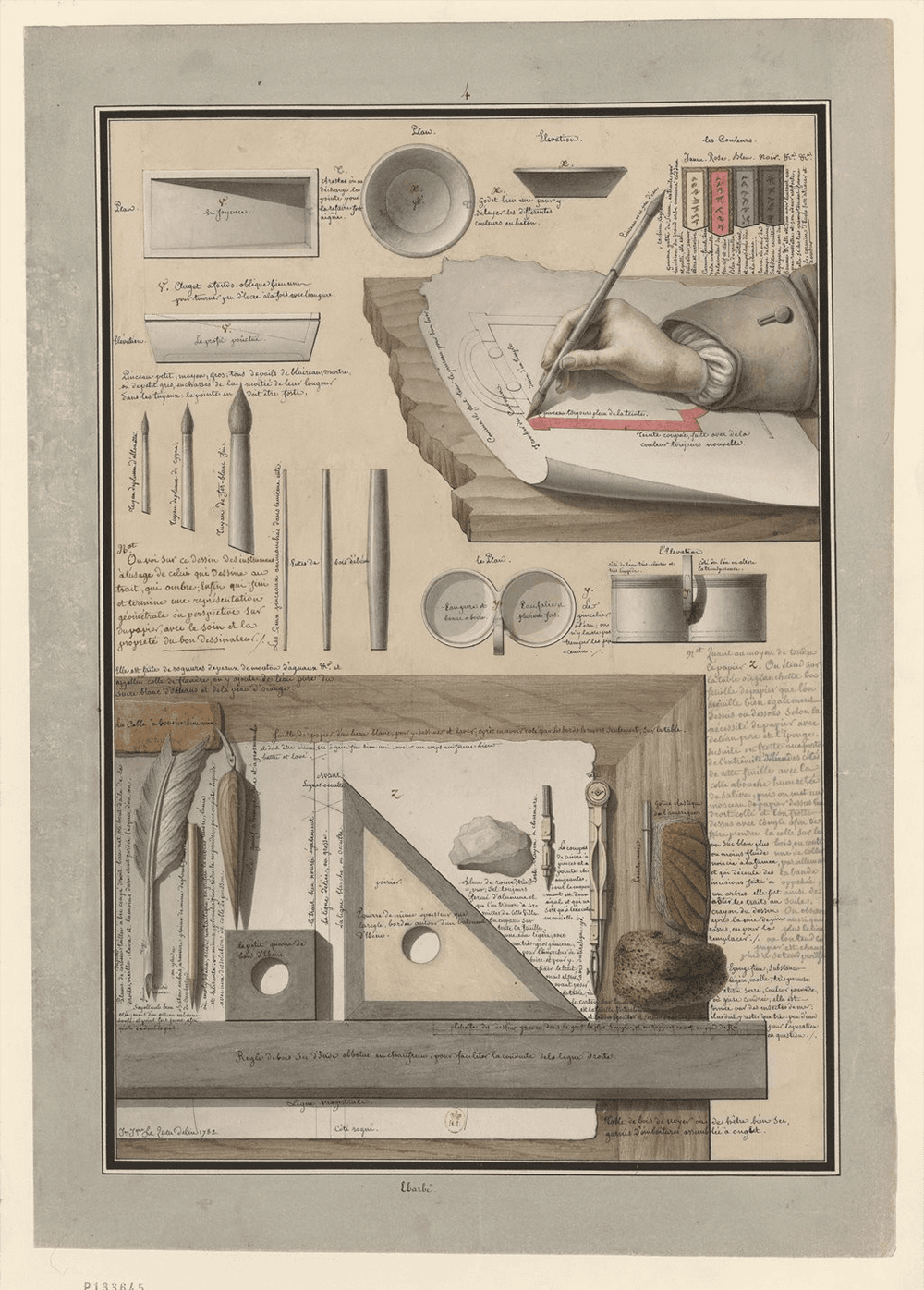

In 2020, The Morgan Library & Museum mounted an exhibition of drawings by the French architect Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757−1826). I appreciated seeing the work firsthand, having studied it many years ago, and I paused for several minutes before a work titled Les Instruments du dessinateur (1782) or The Tools of the Designer. On the meticulously detailed composition of drawing and drafting implements, Lequeu had written, “We see in this drawing the tools to draft, shade in and construct a geometric representation or perspective on paper, with the care and attention to detail of a good designer.”

Lequeu’s drawing and words touched me because, as an architecture student, I loved drafting in pencil and pen and ink, building measured plans, elevations, sections and axons, and constructing models out of chipboard. Those of us who studied design pre-AutoCAD® know the feeling of gliding black ink across Mylar® with a Rapidograph®, the smell of the lead pointer, the ability to — with all our senses — create a nuanced composition of varying line weights that helped us at each step of the process develop the architectural project.

Despite three decades of CAD and BIM software that have indisputably impacted the design process and built environment, some practitioners continue to employ traditional drawing and drafting techniques to design space. Architect Nalina Moses has assembled 220 drawings by over 40 designers of different generations in Single-Handedly: Contemporary Architects Draw by Hand (Princeton Architectural Press, 2019). Moses explores the continued relevance of hand drawing and drafting, and how they integrate the designer’s intentions about materials, structure, space, light and shadow. The book underscores the benefits of a more direct relationship between the designer and the production of the representation, without a software intermediary.

Reading Moses’ book reminded me of the feeling of being a draftsperson at the end of the studio workday — and that to be one is also to be a craftsperson and artist. Even construction details could be put together on a single sheet of paper in a manner that demanded one’s attention to scale, line weight, labeling and composition… in short, each sheet had the potential to be a work of art as well as a means to immerse oneself in the space-shaping process.

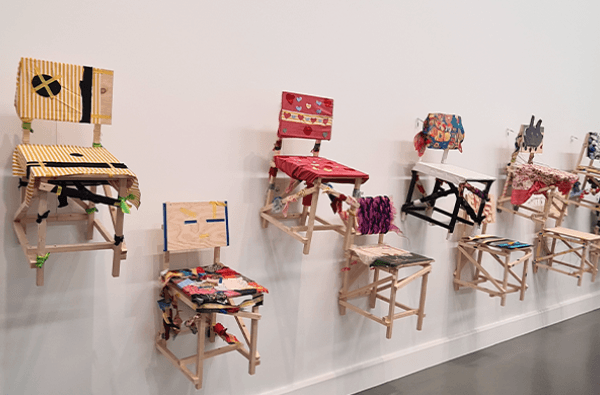

In fact, in the mid- and late-20th century, many drafted and hand-drawn architectural drawings found their way into galleries and were acquired by dedicated collectors. Today, gallerists are noticing a resurgence of interest. Cody Miner is co-director of Modest Common, an art and architecture gallery located in downtown Los Angeles. He notes that young designers are interested in hands-on making as a new creative experience: “These are kind of lost art forms in this post-digital age that we are working through. Architects are using these old techniques but exploring them in a new way. There’s definitely a movement away from the clean, crisp digitization of architecture.”

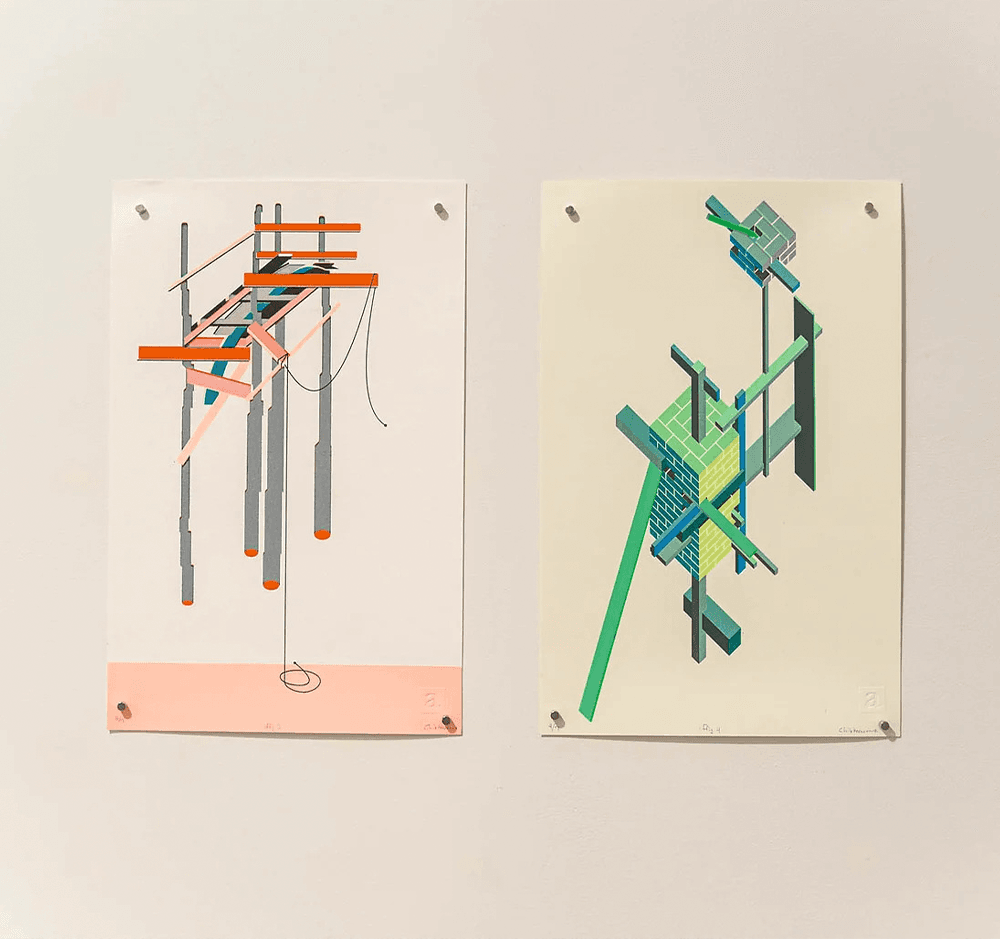

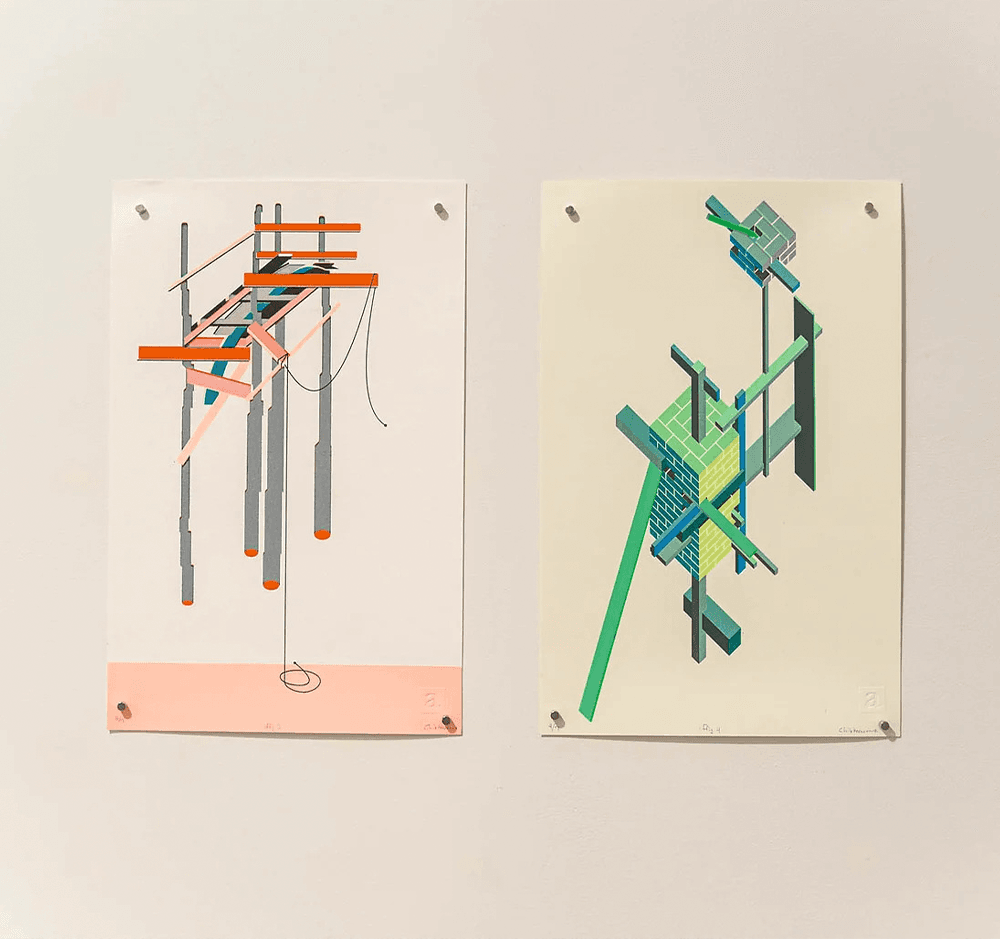

Some designers describe the correlation between making by hand and constructing space as a seamless transition. Owen Nichols, co-director of a83 Gallery and founder of his firm, Chibbernoonie, uses screen printing as an exercise in visioning. “There is something to the physical construction of an image which relates directly to the construction of a building. The layers of ink used to produce a screenprint, for us, translate in terms of layers and seeing through the volumes of a space.”

Drafting or printing on paper or another material not only serves as a grounding element, tying the creator to the present; it can also enhance understanding of a design in a way that a digital image cannot. “I do think there is a relationship between these analog processes, and ways of thinking about approaches to building and making spaces,” says Jesse LeCavalier, who runs his own research and design firm and directs Cornell University’s Urban Design program. “There’s a reason why people do mockups — to understand. I think there is a limit to what a simulation can do, and a physical thing can often exceed it.”

Personally, I acknowledge my nostalgia for hand drafting while maintaining a pragmatic acceptance of digital representation. With rapidly changing software technology and file types, however, I do wonder how much of our digital representation — the bulk of our body of work — is going to last. Owen Nichols believes that designers will always experiment with a range of materials and techniques to create form, but that the imprint of the hand has a lasting impact. “I think people are starting to realize that the production of actual artifacts is valuable because it allows for life beyond the original intention of the image.”

In 2020, The Morgan Library & Museum mounted an exhibition of drawings by the French architect Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757−1826). I appreciated seeing the work firsthand, having studied it many years ago, and I paused for several minutes before a work titled Les Instruments du dessinateur (1782) or The Tools of the Designer. On the meticulously detailed composition of drawing and drafting implements, Lequeu had written, “We see in this drawing the tools to draft, shade in and construct a geometric representation or perspective on paper, with the care and attention to detail of a good designer.”

Lequeu’s drawing and words touched me because, as an architecture student, I loved drafting in pencil and pen and ink, building measured plans, elevations, sections and axons, and constructing models out of chipboard. Those of us who studied design pre-AutoCAD® know the feeling of gliding black ink across Mylar® with a Rapidograph®, the smell of the lead pointer, the ability to — with all our senses — create a nuanced composition of varying line weights that helped us at each step of the process develop the architectural project.

Despite three decades of CAD and BIM software that have indisputably impacted the design process and built environment, some practitioners continue to employ traditional drawing and drafting techniques to design space. Architect Nalina Moses has assembled 220 drawings by over 40 designers of different generations in Single-Handedly: Contemporary Architects Draw by Hand (Princeton Architectural Press, 2019). Moses explores the continued relevance of hand drawing and drafting, and how they integrate the designer’s intentions about materials, structure, space, light and shadow. The book underscores the benefits of a more direct relationship between the designer and the production of the representation, without a software intermediary.

Reading Moses’ book reminded me of the feeling of being a draftsperson at the end of the studio workday — and that to be one is also to be a craftsperson and artist. Even construction details could be put together on a single sheet of paper in a manner that demanded one’s attention to scale, line weight, labeling and composition… in short, each sheet had the potential to be a work of art as well as a means to immerse oneself in the space-shaping process.

In fact, in the mid- and late-20th century, many drafted and hand-drawn architectural drawings found their way into galleries and were acquired by dedicated collectors. Today, gallerists are noticing a resurgence of interest. Cody Miner is co-director of Modest Common, an art and architecture gallery located in downtown Los Angeles. He notes that young designers are interested in hands-on making as a new creative experience: “These are kind of lost art forms in this post-digital age that we are working through. Architects are using these old techniques but exploring them in a new way. There’s definitely a movement away from the clean, crisp digitization of architecture.”

Some designers describe the correlation between making by hand and constructing space as a seamless transition. Owen Nichols, co-director of a83 Gallery and founder of his firm, Chibbernoonie, uses screen printing as an exercise in visioning. “There is something to the physical construction of an image which relates directly to the construction of a building. The layers of ink used to produce a screenprint, for us, translate in terms of layers and seeing through the volumes of a space.”

Drafting or printing on paper or another material not only serves as a grounding element, tying the creator to the present; it can also enhance understanding of a design in a way that a digital image cannot. “I do think there is a relationship between these analog processes, and ways of thinking about approaches to building and making spaces,” says Jesse LeCavalier, who runs his own research and design firm and directs Cornell University’s Urban Design program. “There’s a reason why people do mockups — to understand. I think there is a limit to what a simulation can do, and a physical thing can often exceed it.”

Personally, I acknowledge my nostalgia for hand drafting while maintaining a pragmatic acceptance of digital representation. With rapidly changing software technology and file types, however, I do wonder how much of our digital representation — the bulk of our body of work — is going to last. Owen Nichols believes that designers will always experiment with a range of materials and techniques to create form, but that the imprint of the hand has a lasting impact. “I think people are starting to realize that the production of actual artifacts is valuable because it allows for life beyond the original intention of the image.”