— Feature

Pattern Play

History repeats but is reinvented in bold color textiles through the lens of sculptor Elisabeth Kley whose graphic signature is black and white.

by Elaine Markoutsas

“Elisabeth Kley looks for inspiration from global art and architecture histories. And yet she conveys these motifs with a contemporary edge, one that feels both handmade and in motion.””

Pattern lives rent-free in Elisabeth Kley’s mind. Not in dreams, although she dreams in color. Mostly, her creative process is informed by history. She is drawn to such diverse imagery as Roman, Byzantine, Egyptian, Indian, North African, Islamic, and Wiener Werkstätte.

As a painter-turned sculptor, Elisabeth Kley’s signature style has evolved to an über graphic black and white expression, with an almost naïve quality. The art itself morphed from smaller scale sometimes-utilitarian objects to much larger format decorative pieces.

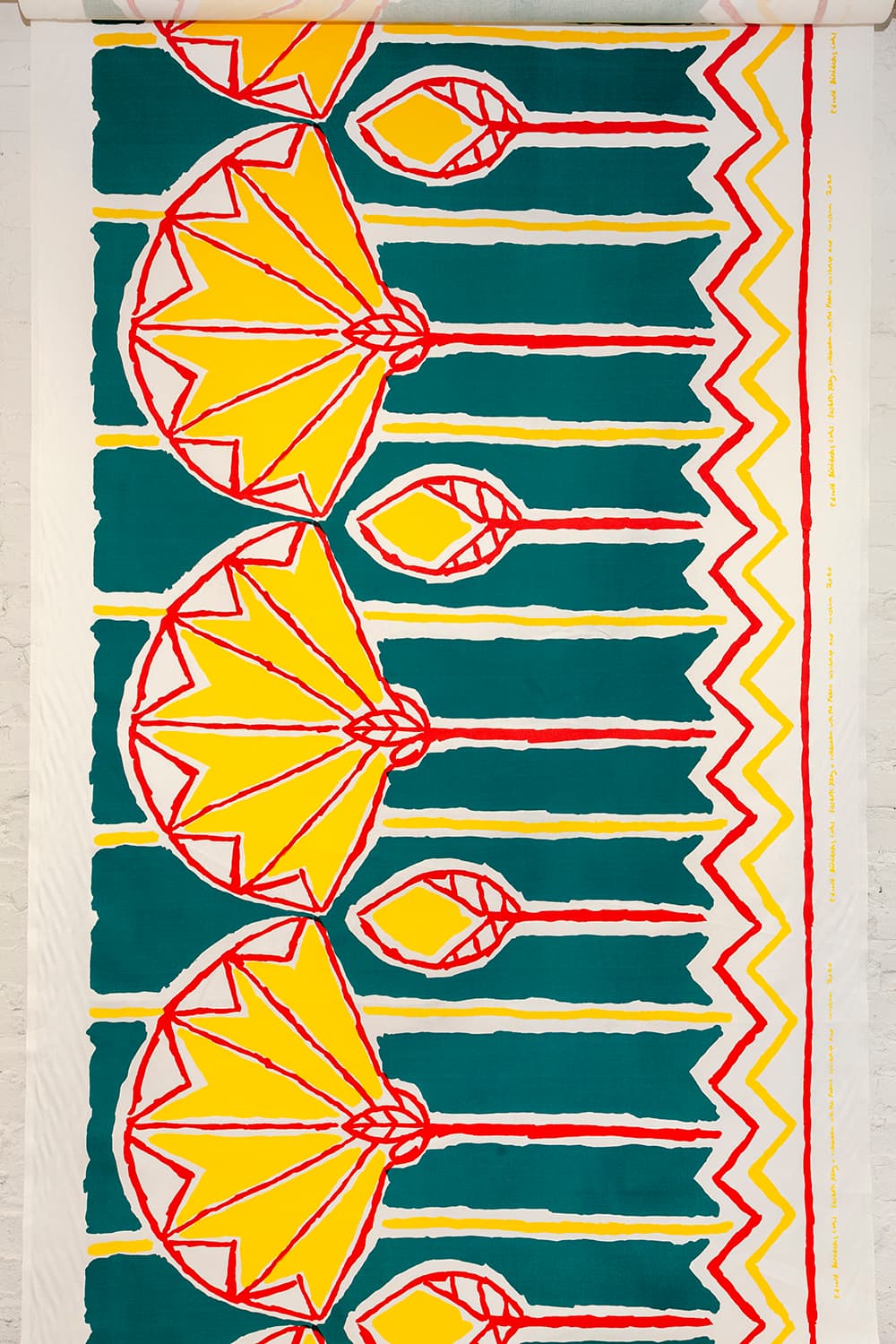

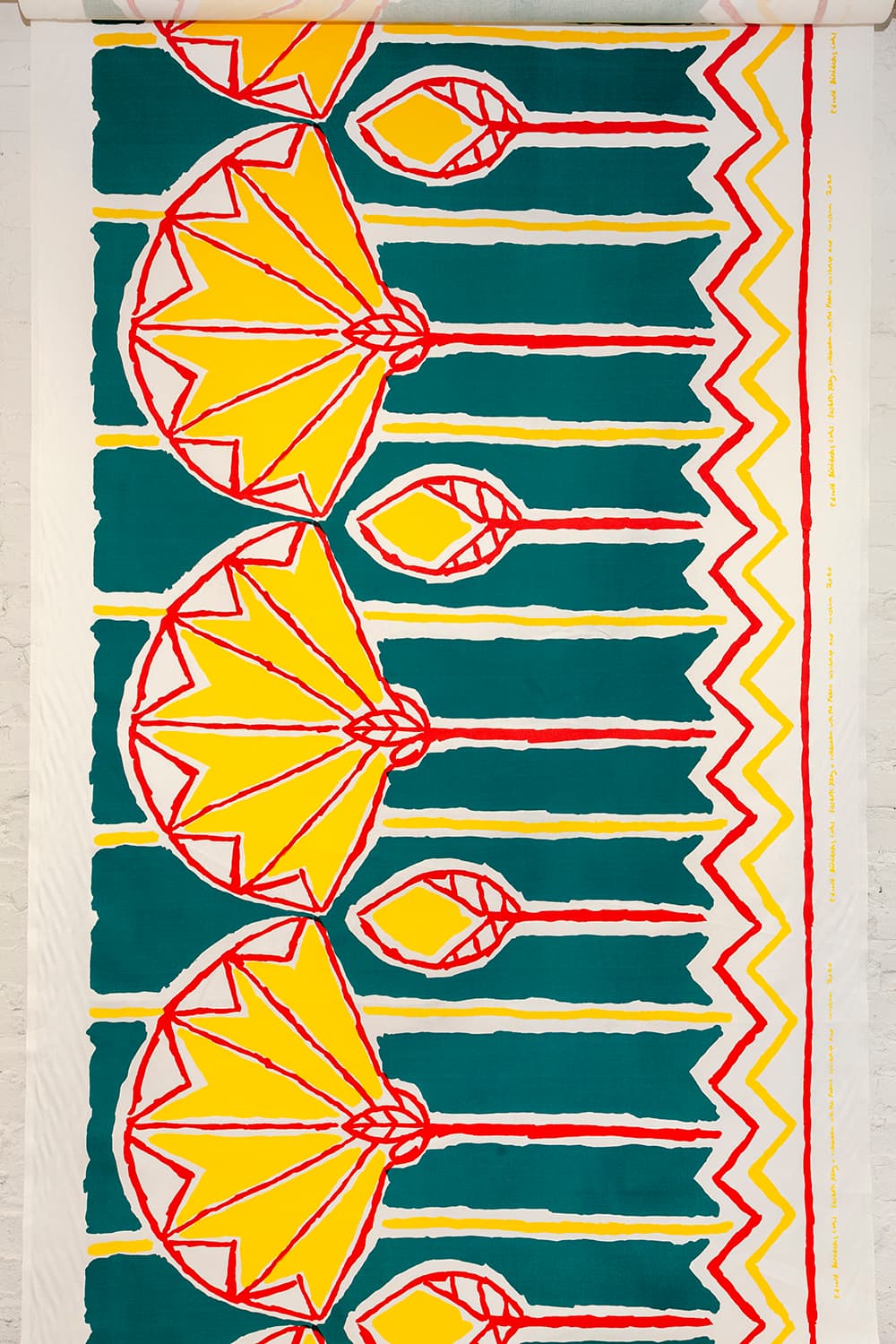

Her first solo exhibit, Minutes of Sand, recently wrapped up at The Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM) in Philadelphia. It revealed a new body of work, plus one in a previously unexplored medium. The Brooklyn-based artist was invited to print fabric with FWM’s world-renowned screen-printing facilities. The intersection of ceramic and painting techniques with printed textiles was compelling as the yardage displayed vivid color — specifically a primary palette underscored by the black and white glazed earthenware. “Even though my sculptures are three-dimensional,” says Kley, “I treat each surface as a sort of painting or drawing.” What was different, she says, was going back to working in color. “Also, the idea of making a fabric was kind of confusing,” she says. “I started off with a small-scale pattern, repeating it. I realized I wanted something more open and bigger. It was a whole evolution.” She focused on more geometrical, simple shapes for the fabric: “I am fascinated by reversal and positive and negative. In textiles, you’re very conscious of the shape of empty space.”

The black and white ceramics were inspired by Egyptian art downloaded from the internet, and in books and photos she took in museums, as she ferreted out details that caught her eye. The screen-printed fabrics are actually linked to early 20th century textiles. A bold yellow lotus on black ground design was derived from a 1918 Egyptian motif for a curtain by Edouard Benedict. The curling red line on a dark blue ground, a familiar wave pattern found in many cultures, was inspired by a fabric design from the late 1910s by Leon Bakst, who designed opulent sets and costumes for the Ballets Russes. “This design was featured in a show I saw at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World in 2019 that focused on the influence of classical Greece and ancient Egypt on Bakst and other designers,” Kley says.

Kley made up the third design, relating it to pieces in theshow, perhaps subconsciously channeling Roman mosaics.For color, Kley experimented with “lots and lots of bottles of colored inks,” mainly Dr. PH Martin’s Hydrus watercolor, which she likes for its texture, lightfastness, and mixability.She especially liked red and the way it spread. “The more I expanded and simplified the designs, the more sensual the color.” Her process was painting multiple designs on 18-by-24 inch sheets of paper. “When I was getting more sure of what I wanted, I cut (lengths) to the same size as the fabric for screening (four feet wide by 30 feet long).” Kley designed and painted the translucent mylar sheets. They were then photographed by the team onto the screen and screen printed. “They took my designs and blew them up on the computer. There was one sheet for each color. They placed the pieces of mylar film over the blowups they made, painting each in black. Then, they took to the darkroom and exposed it on the screen. Three screens for each design; layers of color were laid on the screen, then squeegeed across.”

Two artist-designed interiors continue to inspire Kley: Matisse’s sparse, light-filled chapel in Vence, France and the ornate layering of rich velvet textiles in the Fortuny Palace in Venice. “I feel that my installation is visually somewhere in between those extremes: open graphic shapes played off of intricately detailed patterns.” Pattern is the connective tissue. “I like the repetition and transformation of the design motifs of cultures over time.” Kley points to Egyptian, Roman and Greek motifs being reimagined in Europe both by Empire and Neoclassical designers, and then by the Ballets Russes. Or reimagined Islamic environments in houses of Pierre Loti and D’Annunzio or Natacha Rambova channeling Beardsley in her design for the film Salomé. “Pattern resonates with me because of what it does to space, how it can overwhelm,” says Kley, whose next show is September 2022 at the Canada Gallery in New York.

With a desire to upscale the ceramics even more, she plans to spend a few weeks at Cerámica Suro in Guadalajara, Mexico, where she can experiment with larger commercial kilns. She still might opt to stick with her limited 25-inch-tall kiln and stack pieces because of the logistics of moving massive ones. She also may include more textiles, perhaps exploring other techniques like stamping. Or even batik because of its serendipity. “I love the way color sits on the fabric,” she says. “Seeing that fabric on the wall is amazing.”

Elaine Markoutsas is a Chicago-based freelance design writer and editor.

Pattern lives rent-free in Elisabeth Kley’s mind. Not in dreams, although she dreams in color. Mostly, her creative process is informed by history. She is drawn to such diverse imagery as Roman, Byzantine, Egyptian, Indian, North African, Islamic, and Wiener Werkstätte.

As a painter-turned sculptor, Elisabeth Kley’s signature style has evolved to an über graphic black and white expression, with an almost naïve quality. The art itself morphed from smaller scale sometimes-utilitarian objects to much larger format decorative pieces.

Her first solo exhibit, Minutes of Sand, recently wrapped up at The Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM) in Philadelphia. It revealed a new body of work, plus one in a previously unexplored medium. The Brooklyn-based artist was invited to print fabric with FWM’s world-renowned screen-printing facilities. The intersection of ceramic and painting techniques with printed textiles was compelling as the yardage displayed vivid color — specifically a primary palette underscored by the black and white glazed earthenware. “Even though my sculptures are three-dimensional,” says Kley, “I treat each surface as a sort of painting or drawing.” What was different, she says, was going back to working in color. “Also, the idea of making a fabric was kind of confusing,” she says. “I started off with a small-scale pattern, repeating it. I realized I wanted something more open and bigger. It was a whole evolution.” She focused on more geometrical, simple shapes for the fabric: “I am fascinated by reversal and positive and negative. In textiles, you’re very conscious of the shape of empty space.”

The black and white ceramics were inspired by Egyptian art downloaded from the internet, and in books and photos she took in museums, as she ferreted out details that caught her eye. The screen-printed fabrics are actually linked to early 20th century textiles. A bold yellow lotus on black ground design was derived from a 1918 Egyptian motif for a curtain by Edouard Benedict. The curling red line on a dark blue ground, a familiar wave pattern found in many cultures, was inspired by a fabric design from the late 1910s by Leon Bakst, who designed opulent sets and costumes for the Ballets Russes. “This design was featured in a show I saw at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World in 2019 that focused on the influence of classical Greece and ancient Egypt on Bakst and other designers,” Kley says.

Kley made up the third design, relating it to pieces in theshow, perhaps subconsciously channeling Roman mosaics.For color, Kley experimented with “lots and lots of bottles of colored inks,” mainly Dr. PH Martin’s Hydrus watercolor, which she likes for its texture, lightfastness, and mixability.She especially liked red and the way it spread. “The more I expanded and simplified the designs, the more sensual the color.” Her process was painting multiple designs on 18-by-24 inch sheets of paper. “When I was getting more sure of what I wanted, I cut (lengths) to the same size as the fabric for screening (four feet wide by 30 feet long).” Kley designed and painted the translucent mylar sheets. They were then photographed by the team onto the screen and screen printed. “They took my designs and blew them up on the computer. There was one sheet for each color. They placed the pieces of mylar film over the blowups they made, painting each in black. Then, they took to the darkroom and exposed it on the screen. Three screens for each design; layers of color were laid on the screen, then squeegeed across.”

Two artist-designed interiors continue to inspire Kley: Matisse’s sparse, light-filled chapel in Vence, France and the ornate layering of rich velvet textiles in the Fortuny Palace in Venice. “I feel that my installation is visually somewhere in between those extremes: open graphic shapes played off of intricately detailed patterns.” Pattern is the connective tissue. “I like the repetition and transformation of the design motifs of cultures over time.” Kley points to Egyptian, Roman and Greek motifs being reimagined in Europe both by Empire and Neoclassical designers, and then by the Ballets Russes. Or reimagined Islamic environments in houses of Pierre Loti and D’Annunzio or Natacha Rambova channeling Beardsley in her design for the film Salomé. “Pattern resonates with me because of what it does to space, how it can overwhelm,” says Kley, whose next show is September 2022 at the Canada Gallery in New York.

With a desire to upscale the ceramics even more, she plans to spend a few weeks at Cerámica Suro in Guadalajara, Mexico, where she can experiment with larger commercial kilns. She still might opt to stick with her limited 25-inch-tall kiln and stack pieces because of the logistics of moving massive ones. She also may include more textiles, perhaps exploring other techniques like stamping. Or even batik because of its serendipity. “I love the way color sits on the fabric,” she says. “Seeing that fabric on the wall is amazing.”

Elaine Markoutsas is a Chicago-based freelance design writer and editor.

“Elisabeth Kley looks for inspiration from global art and architecture histories. And yet she conveys these motifs with a contemporary edge, one that feels both handmade and in motion.””