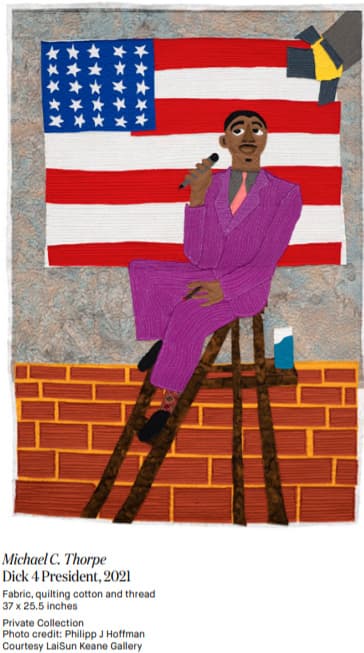

“Basically, it’s all about trying to understand and figure out this new life of being a full-time artist,” Michael C. Thorpe says of his new solo show, “Meandering Thoughts,” at LaiSun Keane in Boston.

Thorpe grew up in Boston with a quilting mother and aunt, but with the exception of a piece he made at 8, quilting took a backseat to sports. “I wanted to be the next Kobe Bryant,” he says. “That’s all I cared about — like, 22 hours of the day I spent playing basketball.” Although he played ball at Emerson College, where he also studied photography, he faced fierce competition to become the next Kobe. Later, as a photographer, he again fought to stand out in a crowded field. Quilting, however, gave him entrée into a rarefied world in which he could easily differentiate himself — and afford him the opportunity to redefine the medium.

“I was the only dude,” he says, of the historically women dominated quilting community. “In the Northeast, because it’s very different than in the south, I was the only black person in these quilting spaces.” Thorpe is biracial and was raised by his white mother. “It could have been alienating,” he continues, “but for my luck and good fortune, it was very embracing. I think of it a lot as a small-town kid who was the basketball star going off to the big university and, like, the whole small town was just rooting for him, and that’s how I feel right now with my art. I have this community that’s just cheering me on.”

For his first show, Thorpe split his focus between figurative and text-based styles — both unusual subjects for quilts. When making portraits of friends, family, and basketball heroes, Thorpe relies on photos as his primary starting point. He’ll create a sketch based on an image, then lay blocks of fabric, like pieces of a puzzle, over the sketch before stitching them together on a quilting machine. For the text-based quilts, Thorpe strings together snippets of found poetry into phrases such as “Shes eating watermelon/she must be half black.” “Whenever I see something that just clicks with me,” he says, “I’ll write it down, and I have, like, an ongoing poem. Basically, it’ll make itself. And once that is done, it’s almost like free jazz — it’s, like, trust the concept, not the music.”

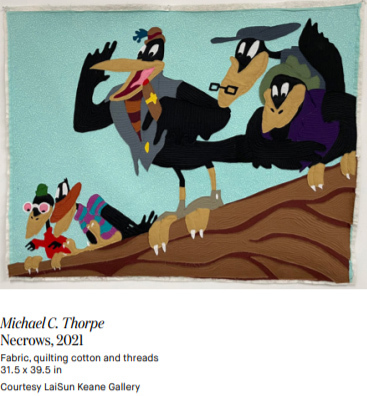

His new show expands his subject range to include landscapes, still lifes, and even cartoons. “I constantly think about art and how people get put in pigeonholes where they only paint people, or they only paint landscapes,” he says. “One of my biggest influences is David Hockney, and David Hockney paints everything.” One of his favorite recent pieces is “Necrows” (a play on “negroes”), depicting the controversial black crows from Disney’s Dumbo. The quilt is an exploration of the artist’s love-hate relationship with Disney and its enduring history of racism. In Dumbo, the main crow character is named Jim Crow — the Jim Crow laws enforced segregation in the American South — and voiced by a white man “talkin’ jive.” “It’s very fascinating to look at Disney and see how often they don’t allow people of color to, like, live in their bodies,” Thorpe says. “Even in the new movie Soul, it’s really wild to me that they literally killed a black man and then had a white woman take over his body.”

Thorpe cites many artistic influences as he meanders toward defining himself as an artist. He likens his text based works to the nonsensical poetry of Dadaism, the avant-garde movement that sprung up in Europe as a reaction to the horrors of World War I. His other artistic influences span Jean-Michel Basquiat and contemporary African American painter Henry Taylor to the generations of Black women producing quilts in Gee’s Bend, an isolated town in Alabama.

Even as he borrows from the artistic past, his work is meant to spark happiness in the midst of today’s acute social challenges: racial strife, a global pandemic, and political division. Rather than leading viewers into that darkness, he hopes his body of work sparks their joy. “I look at a lot of artists, especially in New York, who are doing gutwrenching art, and I don’t want to do that, because, for me, it’s 100,000% escapism,” Thorpe says. “I have this outlet with art that just solely makes me happy, and hopefully, it also brings the viewer happiness.”